Home en contactPlantation Tokens English IntroductionInformatie gezochtHet ontstaan van plantagegeldNederlands IndieBrits Noord BorneoCeylonOverig AzieAfrikaZuid AmerikaMidden AmerikaBewerkt plantagegeldVals plantagegeldEcht versus ValsGezocht en aangebodenLiteratuur en websites

TOKENS USED ON TOBACCO PLANTATIONS IN THE NETHERLANDS INDIES

(This introduction was made by Ad Lansen, I’m glad I may use it for this site)

INTRODUCTION

The use of token currency as a substitute for the normal coin circulation on plantations in North and South America and in Asia is a well-known occurrence. At the end of the 18th century, English planters introduced plantation money in the West Indies. Around 1820, they also introduced this kind of payment for labour payment on the coffee and tea plantations on Ceylon, a state of affairs which lasted till about 1890. From about 1870 till 1914 “house-tokens” were also used on tea, rubber and coffee plantations in South India by the English estate owners. Around 1900, plantation tokens were used on tobacco and coffee plantations in Central America: Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Guatemala.

From about 1872 plantation and estate tokens were used, on a large scale, for payment on many tobacco plantations in the so called “ Residence of the East coast of Sumatra” in the Netherlands East Indies. This “money” was used to pay the coolies who worked there on the plantations.The planters established on Sumatra’s East coast started issuing this exchange item in a way which was directly related to the plantation or estate. As their main reason they said that there was a shortage of small change in these areas. But that was not really the main reason: what they really wanted was to get total control of money circulation on the estates. With that, the coolies were obliged to buy their daily supplies in the plantation shops

The coolies received their payment once a month; in the meantime, their purchases were written in their own “debt record book”; as were also, for example, their gambling debts, and fines for insufficient productivity on the plantation. Another thing of minor importance was that, when the coolies left the plantation without permission, they did not have any normal circulating money which was necessary for staying outside the plantation. They, therefore, also had to pay a fine for unauthorised absence from the plantation when visiting family or friends.

DENOMINATIONS ON PLANTATION TOKENS

The currency in which the cash payment of coolie wages was normally made on the “kebons”, the estates, was the “dollar coin”; the so-called “Straits dollar “. The coolies had to pay for their purchases in the “ Kedeh” or “Cadei”, the shops on the estates.

With the development of tobacco cultivation on the east coast of Sumatra, about 1870 in the districts of Asahan, Langkat, Deli and Batoe Bahra, there came into existence new circulating areas for silver coins, i.e. different sorts of silver dollars of foreign countries. During this development, many Chinese coolies were recruited from the southern Chinese provinces and the Straits Settlements ( Malacca). These coolies were used to getting their payment in silver dollars.

The east coast of Sumatra had a very intensive trade relationship with the Malaysian Peninsula with the main important trading points of Singapore and “ Pulau Penang” on the other side of the Straits of Malacca. On the east coast of Sumatra there was the extraordinary situation that, whereas officially the “guilder” was meant to circulate, almost all money transactions took place in foreign currency. Government officials, however, were paid in Dutch currency ! The silver dollars circulating, on a large scale, on the east coast were: the “Pilardollar” ( the Spanish Cob), the Mexican dollar ( Mexican Cob ), the Hong-Kong dollar, the Japanese “Dollar” ( Yen), the French Piaster, the British Trade dollar and the American Trade dollar.

In 1906 the circulation of foreign currency in the Straits Settlements came an an end as a result of intensive measures to remove it. The Netherlands East Indies Government did the same, starting in 1906, ending in 1908. This was definitely the end of a period when foreign currency circulated all over the Netherlands East Indies.The majority of the workers on the plantations and estates were used to being paid in “dollar currency”, sub-divided into the several denominations of these coins. That is why on the plantation tokens the value was given in “dollar” denominations and the big “dollar-issues” most of the time had a “silver- or gold-like” appearance.

VARIATIONS IN SHAPE AND METAL.

In general, the shape of plantation tokens is round. Other types are: square, triangular, pentagonal, octagonal, rectangular, oblong, oblong with clipped corners, oval and eye-shaped ones. The tokens are mainly struck in brass, copper, nickel-plated zinc, bronze, tin, aluminium and silver. Most of these tokens referred to as silver are only silver-plated items. Note that tokens made of nickel-plated zinc, tin and aluminium have the appearance of “silver”.

Some tokens can be identified by such characteristic features as a square or round hole in the centre. These items were specially made for use in areas of Chinese settlement, where the people were familiar with the centrally pierced Chinese cash. Items exist with counterstamps and Chinese chopmarks on them. Some cast tokens are also known.

While most of the plantation tokens were made for use on tobacco plantations and estates on the east coast of Sumatra, some types also circulated on the west coast. Another group circulated on tea plantations on western Java. There was also a coffee plantation on the island of Batjan, in the Molucca’s, where these tokens circulated.

On the tobacco plantations in British North Borneo mainly tokens of British Companies circulated. Some Anglo-Dutch companies also issued their own plantation money. For example the: Amsterdam-Borneo Tobacco Company; the London & Amsterdam Borneo Tobacco Company and the Rotterdam-Borneo Company.

RARITY OF NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES PLANTATION TOKENS

Generally speaking it is true to say that, while some of these plantation tokens are scarce, most are very rare. The scarce serird are from the tobacco estates of Silau, Hessa, Kisaran, Poeloe Radja and Soengei Serbangan, but this only relates to the high denominations of the one and half dollar.

Tokens in excellent condition and proof items are, in general, very rare. It is not yet known by many collectors of these tokens that the small denominations are much rarer than the big ones.

Even now, it is unknown where the majority of these tokens were made. A small group appears to have been struck in Germany by Lauer Nürnberg, a medallion and token factory in Nürnberg. On some tokens of British North Borneo we find “KB” in small letters, possibly an indication that these items were struck at the mint in Kremnitz in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, nowadays in the republic of Slovakia.

CIRCULATION PERIOD

The earliest issued plantation tokens are these of the Guigne freres, owners of the Soengei Sikambing tobacco plantation on the east coast of Sumatra and the Sumatra Tobacco Company who managed the Tjinta Radja Estate.

The first plantation money circulated around 1875-1876 on these estates. Some tokens bear the year of issue: 1888, 1890, 1891 and 1892. Most of this estate money circulated around 1890 on Sumatra’s east coast. After 1906, the start of the money cleansing operation in the Netherlands East Indies, it can be ascertained that no new issues came into circulation.

GENERAL REVIEW

Almost nothing is known about the issuers, die makers, mintmasters of these different plantation tokens, with a few exceptions for certain big companies such as the Deli Tobacco Company. A lot of these firms were independent estates. Their activities only took place abroad, in the Netherlands East Indies. Their main offices in the Netherlands only had a controlling function and was head financier for further new developments on the plantations.

Those companies received their capital investment from all over Europe: The Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland and Belgium. The management and supervisory staff on the plantations came from all over the world: Dutch, Swiss, Russians, English as well as Germans or Americans. A large proportion of the total amount of these plantation tokens were issued by Herrings & Co. and the multinational Société Financière des Caoutchoucs.

A lot of plantation tokens were issued at the end of the 19th century. That was the period of fast and quick development of tobacco estates in the Netherlands East Indies. The fame of the plantations on Sumatra’s east coast was based upon the cultivation of first-class tobacco, sold all over the world.

The companies obtained their concessions to explore plantations by paying the owners of the land, the Sultan and his Raja’s on the east coast, an annual lease revenue.

Around 1890, at the high point of tobacco cultivation, the Sultan of Deli, resident in Medan, was one of the richest and most influential persons within the Dutch Government on the east coast of Sumatra. In 1872 there were already 17 tobacco plantations in Deli, increasing in the 80s to over 75 in Deli, Langkat, Serdang, Bedagei and Padang. In 1891, 130 tobacco plantations were in production.

In 1890, the price of tobacco declined very strongly due to the increase of import tax on tobacco by the United States. By around 1920, most of the tobacco estates had changed their production from tobacco to rubber.

Some plantation tokens bear the name of Chinese dealers who had close relations with special estates and their employees. These tokens were used in the Chinese shops on the plantations.

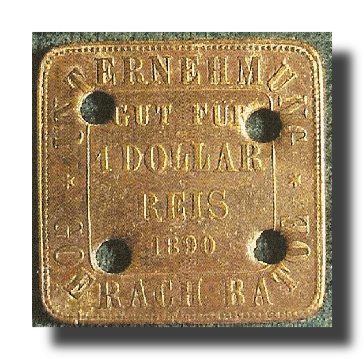

The tokens with German inscriptions such as “Unternehmung” and the value “gut für” were used on a lot of plantations on Sumatra belonging to Mr Herrings, a German. All his plantations produced tobacco which he shipped to Bremen, in Germany, instead of to the biggest auction in Europe, that of Amsterdam. The reason for this was to create a competitive market. This failed and caused him to go bankrupt around 1900.

CONCLUSIONS

Plantation and estate money is still a relatively unknown collecting area. Yet, in spite of being limited, it is an essential part in the numismatic history of the former Dutch East Indies. In this collecting area, one can still find some “unknown” tokens, but be aware of modern forgeries!

To build up a collection of these tokens by type, plantation or estate you have to make a world-wide search to find them.

For the collector of these tokens it is also quite interesting to delve into the history of the development of the tobacco cultivation on the east coast of Sumatra: from wilderness, primeval forest, swamps to cultivated plantations.

REFERENCES

Publications on plantation money is scarce:

C. Scholten’s work: “Munten van de Nederlandsche Gebiedsdelen Overzee” (1951) has a small chapter on plantation money.

Saran Singh, in his book,“The coins of Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei”, (1996-2d edition) gives information about plantation tokens of British North Borneo.

Major F. Pridmore gives some information on the British North Borneo tokens in his book “Coins and Coinages of the Straits Settlements and British Malaya 1786-1951”, (1968).

Jerry Schimmel, in his book “German tokens, part 2”, (1988) gives a small summary of the plantation tokens with German inscription, which circulated on Sumatra’s east coast.

W.W. Woodside gives an account of tokens and banknotes known to him at the time in his “Catalogue of East Indies Estate tokens” (1963).

The most recent book on plantation money of the Netherlands East Indies and British North Borneo is: “Plantage-, Handels-, en Mijngeld van Nederlands-Indie”, (2001) by A.J. Lansen and L.T. Wells Jr. This book provides a great deal of information on plantation and estate money together with a lot of historical information about the estates, plantations, cultivation and owners. (ISBN. 90.70067-16-1 )